Of Lighting A Candle (And Casting A Shadow)

2002-06-23 (last edition of the initial revision)

I fear I will never find anyone

I know my greatest pain is yet to come

Will we find each other in the dark

My long lost love

Beauty of the Beast

Hello again! I just got four Jaguar games from Aldebaran, he’s away over the midsummer feast so he was kind enough to leave me four Jaguar titles, since I own a Jaguar but have no games, heh … I thought I’d wait until tomorrow before knocking myself out though, and do some good right now (or perhaps it’s because the TV is blocked). Ahh, I’ve gotten hold of the new Nightwish CD; Century Child, if you don’t own it already, make sure to do so! They play Finnish metal combined with real cute songs and the main singer is schooled in classic opera, so they have a real cool sound and are probably my favourite musical artists.

We’re up to tutorial number 10; which makes me very glad and proud over the work achieved. This had not been possible without the support of readers and other VIP’s. To celebrate the tenth "anniversary", I’m going to give you something special; a putpixel routine. Actually, that statement was almost meant as a kind of ironic, funny statement. I mean, not until tutorial number 10 do we learn how to code a putpixel routine, in the PC’s MCGA mode for example, this is something you hardly have to learn, it’s implied. However, as anyone who knows this much about programming the ST will know, coding putpixel for the ST is a pain in the butt.

The putpixel will hopefully be a prequel to a tutorial on sprites. Sprites, by the way, are anything that moves on the screen, such as a little spaceship, a funny rabbit or just a bouncing ball. A putpixel routine is a routine designed to put a single pixel on the screen, so on the ST, it lights a single dot in one of 16 colours. To achieve this, four bits have to be changed in four different places in memory, and nothing else must be changed in the screen memory, else too much will be changed.

Let’s first see how we will know which pixel to change. We want to be able to provide information in coordinates, like pixel 160,100, which is about the middle of the screen. The ST would treat any such coordinates with a big question mark, so we have to find a way to translate the coordinates. All pixels come after one another in the screen memory, starting with the top left one, and ending with the bottom right.

This means that X value is of course worth 1 position, since pixel 2,0 is the third pixel on screen. Each Y value is worth as much as the number of X coordinates on one scan line, in the case of ST low resolution; 320. So if we have the coordinate 160,100, that would be the 160 + 100 × 320 = 32161th pixel on screen (one extra is added to the value since we start counting from 0). The total number of pixels on screen is 320 × 200 = 64000 pixels, which is about twice as much as 32160, so the formula seems to work. However, this won’t work on a ST, because we can’t simply count pixels that easily.

The information for a single pixel is contained in four bits in four consecutive words, one bit in each word. So, instead what we need to know is at what word the first bit is, and which bit exactly it is we want to deal with. There are 16 bits in each word, by dividing our X value with 16, we will get the number of word clusters to count in the result, and the exact bit in the remainder.

Here’s why: suppose we want the 19th pixel, this would mean jumping over the first word cluster, which contains information for 16 pixels, and then manipulate the third most significant bit in the next word cluster. 19 / 16 = 1.1875, which means we get the result 1 and the remainder 16 × 0.1875 = 3, it works! So, given the ST’s screen memory configuration, how exactly will we treat coordinate 160,100?

We assume the screen memory points to the start of the screen memory. First, the Y

coordinate, which is the simplest; each scan line is 160 bytes, so multiply the Y coordinate

with 160 and add it to the screen address. Then divide the X value with 16, multiply the

result with 8 and add to the screen memory. Why 8? Because each word cluster that we are

to jump over is 8 bytes; two bytes to a word and four consecutive words. Now, the screen

memory points to the first word of the four consecutive words we need to alter, in each word

we want to alter one bit. The exact bit is obtained from the remainder of the X division. There

may be other intricate methods, but this one is robust, straightforward and good for learning.

Supposing a0 points to the beginning of screen memory, d0 holds the X-coordinate and d1

holds the Y-coordinate, this is how it’s done.

mulu.w #160, d1 ; 160 bytes to a scan line

add.l d1, a0 ; add y value to screen memory

divu.w #16, d0 ; number of clusters in low, bit in high

clr.l d1 ; clear d1

move.w d0, d1 ; move cluster part to d1

mulu.w #8, d1 ; 8 bytes to a cluster

add.l d1, a0 ; add the cluster part to screen memory

clr.w d0 ; clear out the cluster value

swap d0 ; put the bit to alter in low part of d0There is some magic worked here with high and low parts of the data registers. With high and low part, we mean the two first, and two last bytes of the register, thus the high part is the first 16 bits, and the low part the last 16 bits (reading from left to right). By performing instructions with word size, you only affect the lower part of a register, and leave the higher part unchanged.

The divu instruction, leaves the result in the low part and the remainder in the high part of

the register. After the divu, the move.w will only move out the lower part, the cluster part, of

d0. Following is a multiplication on the cluster value, and an addition to screen memory.

Finally, clear out the cluster part of d0, and a swap instruction. The swap instructions flips the

high and low part of a register, so now d0 neatly holds only the value for the bit to be

changed, and a0 points to the correct place.

So, now that we know where to change, how do we know what to change? We will have a

value between 0 and 15, that is supposed to be put in those four bits in the screen memory

(the colour of the pixel). We can’t just move in the data, we could devise some plan with bset

and bclr instructions, but that may be clumsy and will probably involve branches for testing,

which is slow. Instead, we will use our knowledge of masks and Boolean algebra to solve the

problem.

By putting the colour data in the high part of a register, we can then rotate the least

significant bit of the colour into the lower part, and then do a shift on only the lower part of

the register, to put the colour bit in the correct place; mask prepared! Suppose we have the

colour value in d2, and the number of bits to change in d0, obtained from the example

above, this is how it works.

swap d2 ; put colour value in high part

lsr.l #1, d2 ; put one bit of colour in shiftable position

lsr.w d0, d2 ; shift by number in d0Memory will perhaps look something like this, d1 = 5.

| High part | Low part | |

|---|---|---|

d2 |

%0000000000000000 |

%0000000000001011 |

swap d2| High part | Low part | |

|---|---|---|

d2 |

%0000000000001011 |

%0000000000000000 |

lsr.l #1, d2| High part | Low part | |

|---|---|---|

d2 |

%0000000000000101 |

%1000000000000000 |

lsr.w d0, d2| High part | Low part | |

|---|---|---|

d2 |

%0000000000000101 |

%0000010000000000 |

Ah, now the lower part of d2 will hold a terrific mask, we have one bit set, the one bit that

we want to alter in screen memory, a simple ORing of the mask will make sure that the bit is

set in screen memory, then we just add two to the screen pointer, and repeat the process.

Wrong! Problem is, depending on our value, we want to either clear or set the bit, as you can

see, on the third run through, the bit should be cleared, not set (the third bit counting from

the left in the colour value is 0). If we just OR in the mask, and the bit we want to clear in

the screen memory, is set to begin with, we will end up with a set bit where we want a

cleared bit. Buh, that sounded awful, example! This is how it will look the third run through

| High part | Low part | |

|---|---|---|

d2 |

%0000000000000001 |

%0000000000000000 |

note how the fifth most significant bit in the lower part is not set.

Screen memory |

%1111111111111111 |

By ORing d2 with the screen memory, we won’t be clearing out the fifth most significant bit in

the screen memory, although we need it to be cleared in order for the pixel to have the

correct value. So, before ORing in our mask, we need to make sure the bit is cleared. This is

done by ANDing in a mask with all bits set except the one bit we want to change. Mask

preparation looks like this.

move.w #%0111111111111111, d1

ror.w d0, d1d1 |

%11111011111111111 |

The ror instruction, for ROtateRight, will rotate the register, making sure that whatever goes

out the right (or left) will then come in to the left. Thus, if the least significant bit is 0, a 0 will

me moved in the most significant bit, if it’s a 1, a 1 will be moved in. The difference between

a logical shift and a rotate, is that a logical shift will move in 0’s, while rotate will move in

whatever went out. Examine Motorola 68000 Instruction Execution Times if

you wish to further your knowledge on this, there are also arithmetic shifts, but I don’t use them

here. Now, by first ANDing in the clear mask, we can then safely or in our pixel mask, like so.

swap d2 ; colour in the high part of d2

move.w #%0111111111111111, d1

ror.w d0, d1 ; clear mask prepared

lsr.l #1, ; d2 shift in the next colour bit

ror.w d0, d2 ; shift colour bit into position

and.w d1, (a0) ; prepare with mask (bclr)

or.w d2, (a0)+ ; or in the colour

clr.w d2 ; clear the old used bitThen just repeat that over and over, or rather, three times more. The only thing not covered before is the last line, clearing out the old used bit, without this, remnants might be left on the next time around. This is one way of putting a pixel to screen. Bit planes make a putpixel routine so incredibly slow and clumsy. This though, is just a generic putpixel routine, a pixel routine designed for a specific purpose might be much faster, involving only one bit plane perhaps. You don’t have to mess around with all four bit planes every time, say you only want to use four colours for your stuff, then just leave two bit planes alone, since they aren’t needed, this will speed up things. This is the entire putpixel routine.

putpixel:

; a0 screen address

; d0 X coordinate

; d1Y coordinate

; d2 colour

mulu.w #160, d1 ; 160 bytes to a scan line

add.l d1, a0 ; add y value to screen memory

divu.w #16, d0 ; number of clusters in low, bit in high

clr.l d1 ; clear d1

move.w d0, d1 ; move cluster part to d1

mulu.w #8, d1 ; 8 bytes to a cluster

add.l d1, a0 ; add the cluster part to screen memory

clr.w d0 ; clear out the cluster value

swap d0 ; put the bit to alter in low part of d0

; now a0 points to the first word of the bitplane to use

; d0.w holds the bit number to be manipulated in the word

swap d2 ; colour in the high part of d2

move.w #%0111111111111111, d1

ror.w d0, d1 ; clear mask prepared

rept 4 ; do this 4 times

lsr.l #1, d2 ; shift in the next colour bit

ror.w d0, d2 ; shift colour bit into position

and.w d1, (a0) ; prepare with mask (bclr)

or.w d2, (a0)+ ; or in the colour

clr.w d2 ; clear the old used bit

endr

rte return form putpixel

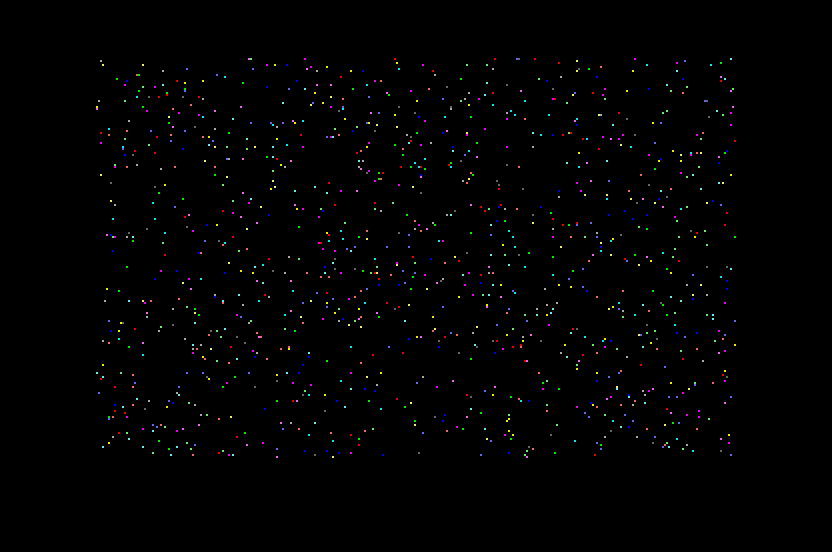

; end putpixelThat was that. A nice putpixel routine to use for our convenience, slow as hell because of two multiplications and one division. Because this is a tutorial, and I want to push against practical use, I’ve also written a stupid little program that puts 50 pixels a second on the screen, like a screen saver. However, that program also includes some nice tricks so read on!

The ST has a number of system variables, they are found at very low addresses, starting at

$400 and ending at $516. Like the name suggests, these variables contain lots of special

information on the system, and they can provide quite the shortcut to finding out some

information. For example, $44e, called _v_bas_ad, is a long word containing a pointer to the

screen memory (the logical screen memory). If you just want a quick and dirty program, like

this one, and want to find out the screen address without traps, or hooking it up yourself,

simply read the value here.

move.l $44e, a0 ; a0 points to screen memoryThere are some other useful system variables, which will be presented when the need arises.

If we want to have a screen saver like program, we want to be able to output random pixels,

right? So we need a way to generate a random number. Random numbers are usually

obtained from reading the system clock, and then applying some algorithm to the obtained

value. We don’t want to mess with that, especially not when there is a very nice trap that will

do the job nicely for us. Trap number 17 in XBIOS will generate a 24-bit random number and

put it in d0.

move.w #17, -(a7) ; trap number 17, random

trap #14 ; call XBIOS

addq.l #2, a7 ; clean up stack

; random number in d0Well, a random number of 24-bits is a number between 0 and 16777216. We want values in the range of 0 to a maximum of 319; 0-15 for the colour, 0-319 for the X coordinate and 0- 199 for the Y coordinate. So how can we get the random number "down to our level", so to speak? We could put the random call in a loop, and in the end of each loop check the random value, and if it is to big, just repeat the loop. While this would work, it would be so incredibly slow because the odds of the value falling within parameters are extremely small. However, by first lessening the value, we gain tremendous time.

As we so well know, the colour value consists of 4 bits. By ANDing the random value with

%1111, we effectively set all bits to 0 except the first four (which may be 0 or 1, depending

on the initial value). Thus, our initial random value of 24-bits has been reduced to a 4-bit

value, making it perfect for our needs. The X and Y coordinates however, are a bit different,

since their representation does not consist of a complete set of bits (numbers that do so are

the ones immediately before the powers of 2, i.e. 1, 3, 7, 15, 31, 63, 127, 255, etc). We can’t

simply mask off the X co-ordinate’s unnecessary bits like we did the colour, rather we have to

keep one bit more than what is needed.

The value 319 uses 9 bits, so we will have to AND the X coordinate with %111111111, but

%111111111 = 511, so after masking off the bits in our random value, we’ll have a number

between 0 and 511. Now, we must use a loop to check the value, and make a new random

number if it should prove to be over 319. The odds for the value of being within parameters

are greatly increased though.

get_x

move.w #17, -(a7)

trap #14

addq.l #2, a7 ; get random number

and.l #%111111111, d0 ; make it maximum 511

cmp #319, d0

bgt get_x ; loop until d0 < 320The instruction bgt will branch if the value compared is greater than. This loop then, will loop

until the value in d0 is not greater than 319. The Y coordinate is obtained by doing much the

same thing, but we only need to AND with 8 bits, because the Y coordinate should be < 200,

and 8 bits make up 255. There, all the theory we need, this is the complete source of the

program.

jsr initialise

move.l $44e, a0 ; a0 poins to screen memory

move.w #0, $ff8240 ; black background

move.l #7999, d0

clear

clr.l (a0)

dbf d0, clear ; clears screen to colour 0

main

move.w #37, -(a7)

trap #14

addq.l #2, a7 ; wait retrace

get_x

move.w #17, -(a7)

trap #14

addq.l #2, a7 ; get random number

and.l #%111111111, d0 ; make it maximum 511

cmp #319, d0

bgt get_x ; loop until d0 < 320

move.l d0, d7 ; store x coordinate

get_y

move.w #17, -(a7)

trap #14

addq.l #2, a7 ; get random number

and.l #%11111111, d0 ; make it maximum 255

cmp #199, d0 ; loop until d0 < 200

bgt get_y

move.l d0, d6 ; store y coordinate

move.w #17, -(a7)

trap #14

addq.l #2, a7 ; get random number

and.l #%1111, d0 ; make it maximum 15

move.b d0, d2 ; put colour number in d2

move.l d7, d0 ; put x coordinate in d0

move.l d6, d1 ; put y coordinate in d1

move.l $44e, a0 ; a0 points to screen memory

jsr putpixel ; put pixel on screen

cmp.b #$39, $fffc02 ; space pressed?

bne main ; if not, repeat main

jsr restore

clr.l -(a7) ; clean

trap #1 ; exit

putpixel:

; putpixel routine

; a0 screen adress

; d0 x-coordinate

; d1 y-coordinate

; d2 colour

mulu.w #160, d1 ; 160 bytes to a scan line

add.l d1, a0 ; add y value to screen memory

divu.w #16, d0 ; number of clusters in low, bit in high

clr.l d1 ; clear d1

move.w d0, d1 ; move cluster part to d1

mulu.w #8, d1 ; 8 bytes to a cluster

add.l d1, a0 ; add cluster part to screen memory

clr.w d0 ; clear out the cluster value

swap d0 ; bit to alter in low part of d0

; now a0 points to the first word of the bitplane to use

; d0.w holds the bit number to be manipulated in the word

swap d2 ; colour in the high part of d2

move.w #%0111111111111111, d1

ror.w d0, d1 ; clear mask prepared

rept 4 ; do this 4 times

lsr.l #1, d2 ; shift in the next colour bit

ror.w d0, d2 ; shift colour bit into position

and.w d1, (a0) ; prepare with mask (bclr)

or.w d2, (a0)+ ; or in the colour

clr.w d2 ; clear the old used bit

endr

rts

; end putpixel

include initlib.s

Yes, first a normal initialisation, then the neat trick of putting the screen address in a0,

followed up by putting the background black and clearing the screen. Then, a main routine,

the question here is why I didn’t I use the $70 as described in tutorial 9. The reason is a bit

farfetched, but valid. Because of the random loops, there is a theoretical possibility of the

main routine taking longer than 1/50th of a second, it’s virtually impossible, but it could

happen. If this were to happen, the $70 vector would be called while the previous one were

still being executed, resulting in a crash. With the method I use here, however, there is no

danger of a crash.

Obtaining the X coordinate, as described above, only new thing is storing the coordinate in

d7. This is because the coming random trap for the Y coordinate will destroy everything in

register d0, and then some, register d7 however, is safe. Same goes for the Y coordinate.

Finally, the colour value is obtained, and moved over to d2, then the X and Y coordinates are

moved into their respective registers. These registers could be anything, or a variable or

whatever storage possibility, but the putpixel routine is designed to have the X coordinate in

d0 and the Y coordinate in d1, so this is how it’s supposed to be. After the screen address

has been put in a0, all is set for the putpixel call.

The putpixel routine is exactly as described above, so nothing new there. Signing off with a check for a pressed spacebar, and that concludes the program. Note how I put the putpixel routine in its own subroutine, instead of including it in the main program, which could also have been done. This results in tidier code, the downside being that it takes more time to execute, but time is no issue here.

Speaking of time, I actually think that I’ll fill up some space here with a bit on optimisation, something that will have to come one day or another anyway. There are two multiplications and one division in the putpixel routine, horrible. These can be replaced with shift instructions, but it’s a bit tricky. Each shift either doubles or halves the value in the register. So how do we do a multiplication of 160 and a division by 16, where we also keep the remainder?

First, the Y part; here, we want to have a result equalling d1 × 160. 160 is not a value you

may shift by, since all shift will produce multiplication results of 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256

and so on. However, 128 + 32 = 160, the value we want to multiply with, and when things

come to multiplication, we are allowed to split the multiplication in two and add the result;

d1 × 160 = d1 × 32 + d2 × 128. All we have to do is copy our Y coordinate into another register,

shift one register with 5 (multiplication of 32), shift the other with 7 (multiplication of 128)

and add the results together.

move.w d1, d3 ; copy Y coordinate

lsl.w #7, d1 ; mulu #128,d1

lsl.w #5, d3 ; mulu #32,d3

add.w d3, d1 ; add results together

add.l d1, a0 ; add result to screen addressNote the word size used in all operations. There may still be garbage in the upper part of d3,

but this is never touched in any of the operations. Since the maximum value we will handle is

199 × 160 = 31840 is less than the maximum for a word size, which is 216 = 65536, it’s ok to

only use word size instructions, it also saves time. Our mulu instruction would take a

maximum of 70 clock cycles, but in this case I think it’s 42. The technique of shifting takes

12 + 6 + 2 × 7 + 6 + 2 × 5 + 8 = 58

Heh, seems we wasted time rather than saving. Let that be an important lesson, sometimes the job’s just not worth doing. ☺

So now the X part, first, put the thing in the upper part of d0 with a swap. Now, with a right

shift of 4, we will effectively divide the number by 16, which is what we want to achieve, the

result will be in the upper part, and the remainder will be in the highest bits in the lower part.

Now, what we need to do is simply to put the remainder down in the lowest bits in

d0, so we right shift by 12. The reason for right shifting by 12 is that the remainder takes up

a maximum of 4 bits (remainder maximum is 15, %1111), and 12 + 4 = 16 which is the

number of bits in the lower part of a data register. Unfortunately though, you can’t shift by

12 when shifting with a number, so we’ll just have to divide the shift in one 8 and one 4 part,

8 being the highest number you may shift by.

Swap down the result in the lower part, and shift it left by 3 in order to multiply with 8. We make sure to keep the operation word size in order not to affect the remainder in the upper part. Then, add the result to the address register, but only use a move with word size, in order to only add the multiplied result, and leave the remainder well alone. Lastly, a clear out of the result part and a swap to put everything right for the next part of the putpixel.

swap d0 ; put in upper part

lsr.l #4, d0 ; divide by 16

lsr.w #8, d0 ; shift down remainder ...

lsr.w #4, d0 ; ... by 12 bits total

swap d0 ; result in lower part

lsl.w #3, d0 ; multiply with 8

add.w d0, a0 ; add result to screen address

clr.w d0 ; clear out result

swap d0 ; put remainder in lower partThat was that, now let’s see if this optimisation did us some good. Unoptimized takes about

140 + 6 + 4 + 40 + 12 + 4 + 4 = 210

The division is an approximation. Also, I don’t think we really need to move some data to d1

to manipulate it, so the unoptimized could do some optimization too, but that’s not too

important. Now let’s see what the shift-optimized part will take

4 + 8 + 4 × 2 + 6 + 8 × 2 + 4 + 6 + 3 × 2 + 8 + 4 + 4 = 88

Even though I’m a bit unsure of some values here, it’s obviously quite a save in any case. That was a little taste on how to optimize easy, just replace multiplications and divisions with shifts, sometimes quite a saving, but not always.